kilobeat

a collaborative web-based dsp livecoding instrument

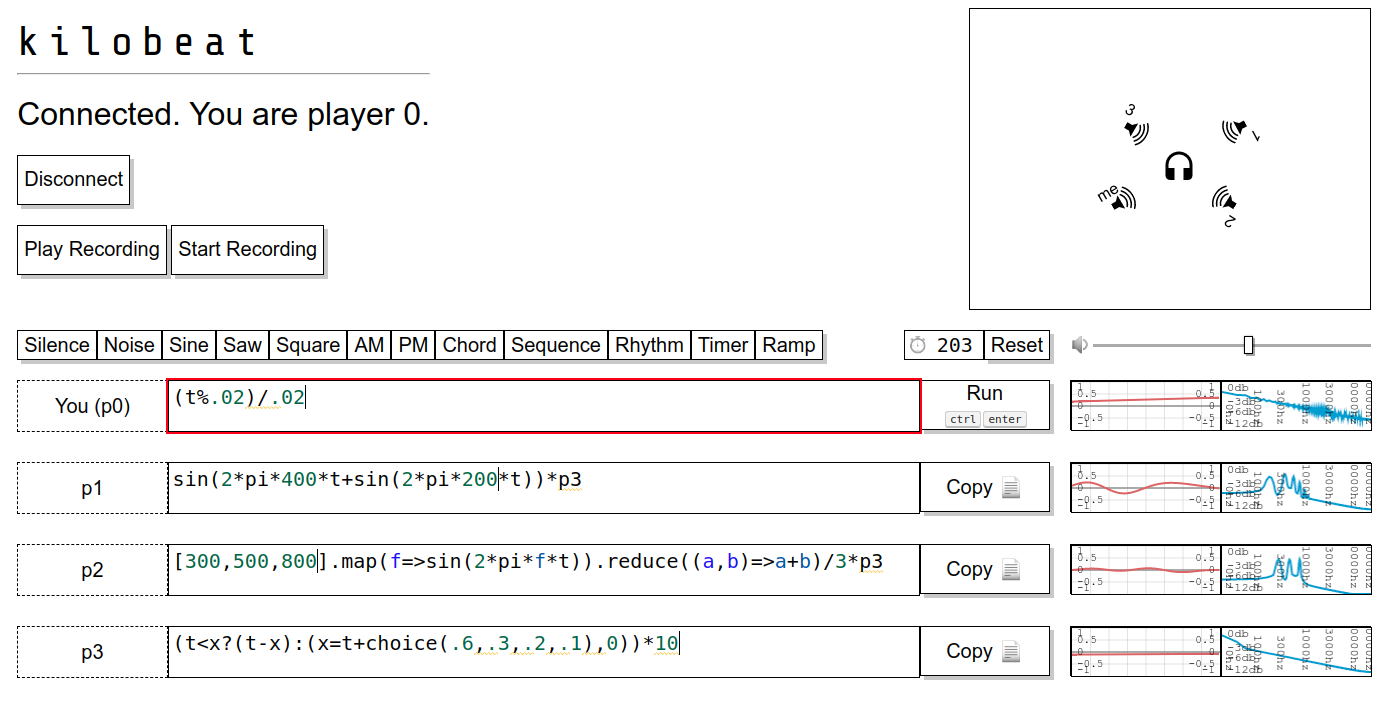

Today, I’m happy to announce the release of kilobeat. Inspired by bytebeat and web-based livecoding platforms, kilobeat is the collaborative web-based DSP livecoding instrument that you’ve been waiting for. Or, with less jargon: kilobeat is a fun music thing you can play with your friends over the Internet.

The core idea is this: some people to get together, and each of them has an instrument. When someone plays, everyone in the room can hear them play. And everyone can see how they’re playing, too. The instrument is light, so people can also move around the room while they play, and this changes where the sound comes from.

This probably sounds pretty normal so far. But in this scenario, everyone has the same instrument: a code box. People play the instrument by putting some code in their box and running it. The code is limited to a single expression. That expression is evaluated to generate each sample of that player’s audio. As players edit their code, everyone else can see their edits (and cursor movements and selections) live.

Since everyone has a small, one-expression code box to type in, each player’s contribution should remain fairly simple: maybe some FM synthesis, maybe a chord or a rhythm. To attain complexity, players can play together! In addition to the usual approach of layering, players can engage in something unique to the medium: plugging in, modular-synthesis-style. That is, one player can plug another player’s instrument into theirs by writing an expression that references the other player’s output. For example, one player could rely on another to modulate their frequency or amplitude.

As the instrument might be unfamiliar, it comes with some presets (listed at the top) to give you some sense of what you can do. These can be combined in any way; some classics are addition (layering), multiplication (amplitude modulation/envelopes), and function composition (passing in one thing as an argument to another, e.g. frequency modulation). Also, players can see their output on an oscilloscope and spectrum analyzer, which can further clarify how things work and who’s doing what.

If all your friends are busy or you just want to try some things out, you can play in offline mode, which allows you to run around and play all the instruments yourself. And if you want to record a performance (online or offline), you can do that, too. The actual performance details (who did what when) are recorded, so the audio may differ on playback. This is sort of akin to a player piano recording the actions of a pianist, rather than recording the sound of the piano. On playback, the keys are struck again, which may sound slightly different than the last time. In the case of kilobeat, the difference may be more significant if players used randomness in their expressions—such recordings are naturally aleatoric.

You can try out kilobeat here with Chrome or Firefox.1

The source is available on GitHub under the MIT license. Check out the README there for more technical details.

Context

Complexity emerging from simplicity is an idea that has long fascinated me. The go-to example is cellular automata, where a couple of simple rules can lead to remarkable structures and behaviors. Language design is another great example—how simple can a language be while still describing everything describable? The question brings to mind answers ranging from the lambda calculus to Brainfuck to Scheme.

The question is a relevant one for composers, who constantly struggle to balance simplicity and complexity as forces opposed. Between dull order and unintelligble chaos, there is some sweet spot always on the move—music that is intelligible, but not transparent. Listenable but not forgettable. Music with a solid surface and substance beneath it.

Bytebeat is a modern take on this question. This musical practice represents compositions as little snippets of code, short arithmetic expressions that generate an audio waveform. People have engaged in this practice over the past several years, identifying constructions and rules that enable them to produce remarkably complex sounds from very short descriptions.2

Some of the surface interest comes from the timbres this tends to produce; integer arithmetic, bit-twiddling, and lo-fi (canonically 8-bit samples at 8 kHz) output invite harsh, retro tones with plenty of harmonics. But beyond the surface, there’s more. Bytebeat compositions are naturally periodic, as the time counter will inevitably overflow. Simple bit-shifting operations allow for controlling the periodicity and building repetitive structures at different levels: at the level of timbre, rhythm, and form, and all gradations in the fuzzy spaces between them. Parts may be overlaid through plain addition, allowing for harmony, counterpoint, syncopation, and anything else you can think of. Traditionally, a composer uses internal processes (formal or not) that deal with these concepts, and this results in the notes on the page (or in the MIDI file or audio recording), but the notes themselves do not specify the process. With bytebeat, it’s all right there—as with the process music espoused by Steve Reich, there’s nothing hidden, but there remain mysteries enough for all.

As a practice, bytebeat is not performative; compositions are like gems to be discovered and admired. Like cellular automata, they play themselves. With kilobeat, I hope to bring human players back into the game, combining the conceptual simplicity of bytebeat with the joy of performing, while contributing another approach to the short but growing list of ways to livecode collaboratively.3 Hence the features oriented towards collaboration: seeing everyone’s code, how they edit it, when they run it, and where they move it in space. All of these performance details are captured and sent to other players, and, in recording mode, they are recorded for playback for some future audience.

There are a few important distinctions between the language of kilobeat expressions and typical bytebeat: most importantly, it uses floating point arithmetic and encourages use of conventional functions (sin & co) over bit manipulation.4 This is in the interest of clarity: ideally what each player is doing (and how they’re doing it) is as clear as possible, for the sake of the audience and other players, while still remaining concise and quick to read and write. This goal is also why kilobeat uses plain Javascript as the language of expressions (rather than a more terse language), mostly avoids adding new built-ins, and features real-time waveform and spectrum displays for each player’s output. In pursuit of the related goal of accessiblity, I made kilobeat web-based to simplify sharing, following the examples of livecoding platforms like Gibber, EarSketch, and Jazzari.

Finally, I’ve been interested in the notion of computational compositions for a while now—that is, compositions that compute, that require the use of a computer (whether human or machine) to realize each time they are played. Today, many compositions are effectively played once to create a recording, and then that recording is listened to again and again, as the definitive representation. I’m interested in compositions that encompass all possible realizations of themselves—where no one recording can definitively contain the whole composition in all of its possibilities. This is closesly related to the concepts of aleatoric music, explored extensively by John Cage and Karlheinz Stockhausen, stochastic music, as pioneered by Iannis Xenakis, and most recently generative music as described by Brian Eno. kilobeat, with its support for recording and playing back performances that may come out differently each time (with the degree depending on how randomness is used), is my own small step in that direction.

Acknowledgements

I used Arthur Cabott’s Audio DSP Playground as my starting point, and adapted spatialization code from Boris Smus’ WebAudio demos. Thanks for making your work open-source.

I developed kilobeat for the course SOUND: PAST & FUTURE in Spring 2020, and for the MIT laptop ensemble (FaMLE). Thanks to Tod Machover and Ian Hattwick for early feedback.

Thank you for reading, and happy hacking!