Remembering f(x)

a cautionary tale and tech specs

A Cautionary Tale

Back in Spring 2019, I took 6.115 (Microcomputer Project Laboratory) at MIT. It’s a fun class with a fairly heavy workload and a memorable instructor, and it’s all about microcomputers: small, embedded systems running your code directly (no OS) and interacting with hardware. The main platforms when I took the course were the 8-bit Intel 8085 (which we programmed in assembly) and the Cypress PSoC 5LP (with a 32-bit ARM core that we programmed in C).

One of the nice things about this class is that your final project can be pretty much anything, so long as it uses one of these platforms and represents a sufficient level of technical understanding. For my project, I wanted to build a multi-effects processor for guitar. This involved using the PSoC to perform DSP, drive a display, and take input from a touchscreen, rotary encoders, and an analog source (the guitar). I dubbed this project f(x).

Okay, but why am I posting about this now? It’s been on the ol’ projects page for some time, and nothing has changed since the demo video.

Well, I have a confession: I goofed. I lost the source code for this project and will never see it again.

What happened?

Did I have a hard drive failure with no backup? No, but that’s close. What actually happened was even more preventable than that.

When developing f(x), I used Cypress’ PSoC Creator to lay out my hardware configuration, compile my code, and flash my firmware. Unfortunately, PSoC Creator is proprietary and Windows-only. I tried it in Wine to no avail, and I could not identify an alternative, so I turned to my last resort: run it in a Windows VM. This worked okay, and I was able to develop f(x) and get it running on the PSoC.

After the semester concluded, I moved, interned, and came back for an M.Eng; I still had my f(x) box and hoped to return to it at some point (at least for inspiration for a future project on a platform with more resources). By January 2020, I was putting together a little portfolio on my website for a grad school application. I wanted to include f(x), and I wanted to include its source code.

At this point I realized that I didn’t have the source code.

Several months prior, I had hit the limit of my laptop’s SSD and had gone hunting for things to get rid of. My disk usage analysis led me to some virtual drives for Windows student VMs. I was so confident that none had anything of import (that wasn’t backed up elsewhere) that I deleted them.

At that time, I may have even been correct. I had a directory shared with VMs which would survive the deletion, and I knew it contained Max patches from 21M.362 and some artifacts from 6.115 (but, as it turned out, not the f(x) source). What’s more, I had a flash drive that probably contained a copy of my submission for 6.115, including source code.

I’d loaned this flash drive to a colleague a few weeks ago so they could flash it with Ubuntu.

Almost out of options, I tried emailing the course staff. If nothing else, my lab notebook would have a full printout of the f(x) source code in an appendix. Unfortunately, too much time had elapsed and the notebook was gone.

Epilogue

For that portfolio, I had no source code to attach, and thus I could only submit my demo video, project proposal, and PSoC hardware schematic. Alas.

Back in November, I uploaded my demo video to YouTube. In February, a commenter asked if I would make the project public; eventually, that prompted this post, as I wanted to give the commenter an explanation as to why I could not, and provide some details for anyone inspired to build something along the same lines. These details are covered in the next section.

For everyone else, I hope this serves as a cautionary tale. If you’re reading this, and you have some project you’re working on, or worked on and recently shelved, back it up now! For shelved projects, the main thing is to put it somewhere such that you 1) won’t forget about it 6 months from now and 2) won’t accidentally throw it out during those 6 months. For those criteria, the safest option is probably to toss it online somewhere, and this is easier than ever. Even if you’re feeling shy about releasing your project, GitHub offers free private repos these days; there’s no excuse.12

Design of f(x)

Hardware

I intended f(x) to support an arbitrary number of effects with a single hardware interface. To that end, I used a touchscreen (HiLetgo ILI9341 2.8”)3 and five clickable rotary encoders. With this hardware, the firmware could readily implement a modal interface, supporting many different effects and interactions with the same hardware.

Aside from the touchscreen and encoders, f(x) consisted of a 1/4” mono audio jack (for guitar input), a 1/8” mono audio jack (for audio output), a DP3T switch,4 and the aforementioned PSoC 5LP (specifically the dev board). Oh, and a lightly used cardboard box from Adafruit, which served as a stylish enclosure.

Hardware-ish

The PSoC is a “programmable system-on-a-chip”. Programmable here refers not only to the CPU, but to the hardware: the PSoC comes with a bunch of analog and digital blocks, which can be configured and routed by the programmer to suit their design.

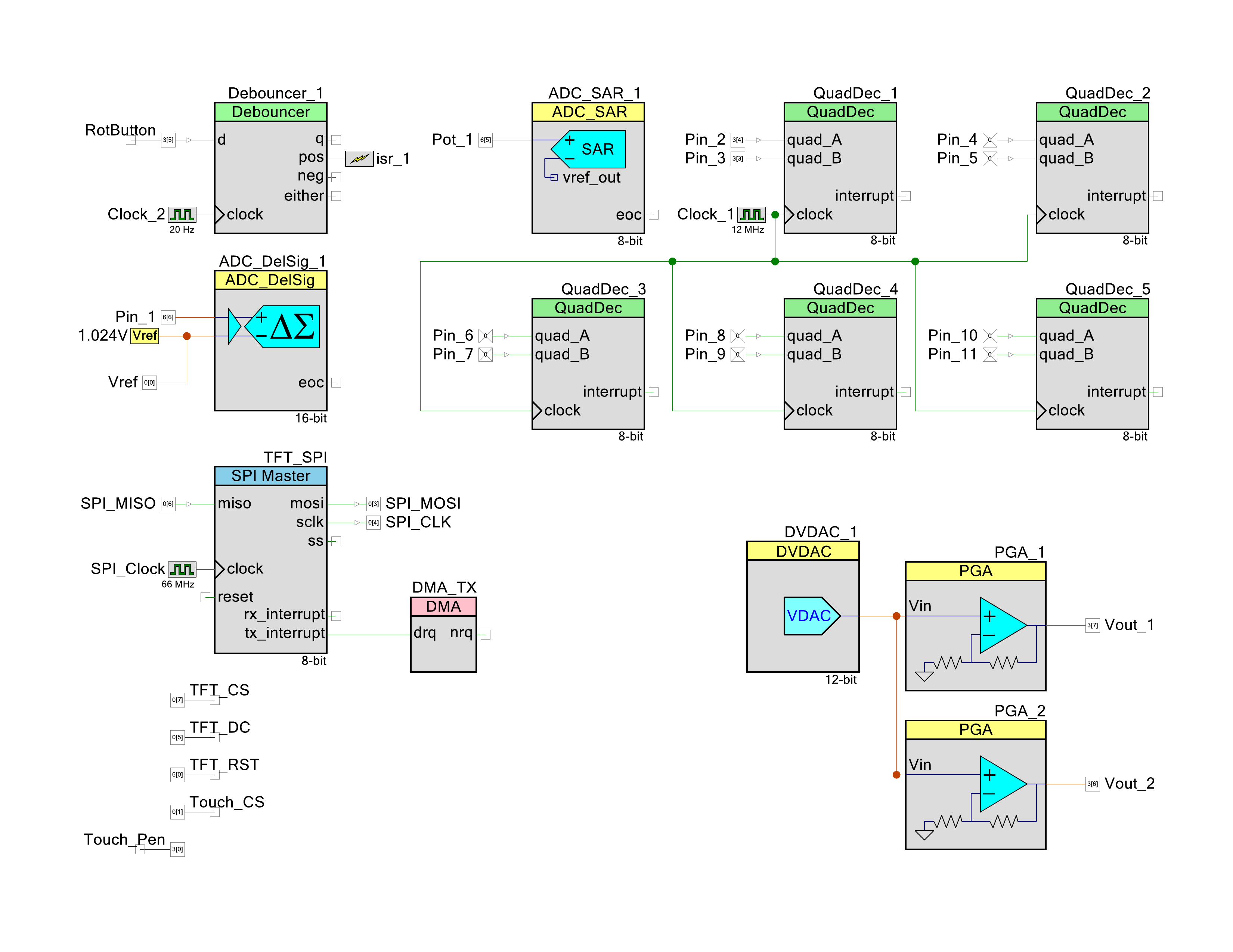

The PSoC Creator project files (which include this configuration) were lost with the source code, but a PDF rendering survived (go figure):

This schematic consists of:

- A delta-sigma ADC for converting analog signals from the guitar into 16-bit samples.

- A 12-bit dithering DAC with amplifiers for converting output samples into an analog signal.

- Five digital blocks for tracking the five rotary encoders.

- A digital block for communicating with the LCD touchscreen over SPI.

- Additional GPIO pins for interfacing with the LCD touchscreen.

- A digital debouncer for one of the rotary encoder’s clicks.

- An 8-bit ADC for an internal potentiometer on the dev board, for debugging; not exposed to the end-user.

Software

The PSoC 5LP includes an ARM Cortex M3 processor. The M3 lacks hardware support for floating-point arithmetic, so, for performance, I ultimately used fixed-point arithmetic for all computations. Also for speed, I used ARM’s CMSIS-DSP library for the FFT (which beat any implementation I could roll on my own).

In the f(x) interface, the touchscreen displays four buttons on the left side, corresponding to four modes:

- Oscilloscope

- Spectrum analyzer (hence the FFT)

- Unused (prints “party on, dude!”)

- Signal chain editor

The oscilloscope and spectrum analyzer do what you’d expect. The spectrum analyzer displays frequencies on a linear, not log, scale. Both operate on the output signal (so you can see the effects).

The signal chain editor is the interesting part. f(x) features a fixed structure of three effects composed together: effect 1 → effect 2 → effect 3. The user can select the effects (choosing what should fill each slot in the chain) and change one parameter for each effect.5

f(x)’s firmware is in C, and the signal chain is essentially an array of function pointers (plus metadata like the effect name, parameter name, etc.). Each effect is implemented as a function that takes a buffer of input samples, a buffer for output samples, and a parameter value.

These effects include:

- Pass through (the default effect, which does not modify its input)

- Delay with feedback (parameter: delay time, limited by available memory)

- Distortion with hard-clipping (parameter: gain)

- Drone: a sine tone added to the input signal (parameter: frequency)

- Bandpass filter (parameter: center frequency)

- Auto-wah (parameter: sweep rate)

Conclusion

f(x) was a fun project, and I wish I had the remains so I could give it a proper burial. I doubt I’d go back to work on it again, but it would have been nice to release it, so that anyone interested might learn from it, and so that I could go back to it for reference or inspiration. Instead, all I can do is write up this post.

When I go back to working in this area (programmable signal processing for musical performance), I’ll probably use a different platform, such as Raspberry Pi (maybe with Pisound) or Bela. One thing I’m still interested in exploring is the possibility of combining livecoding with instrumental performance: that is, livecoding effects, recording snippets of performance and manipulating them, etc.; something between live looping and live coding. Let me know if you know of work in this area I should check out, or if you have any recommendations for DSP platforms that might work well for this.

Here’s a parting video from f(x) development:

Happy New Year,

ijc

-

My fate could also have been averted by a regular backup plan. Unfortunately, this remains on my TODO list. ↩

-

It’s worth noting that using version control for your projects, while certainly a good idea, does not automatically protect you from this fate. Comitting locally isn’t enough; you also have to push! ↩

-

Initially, I used another one. After burning it out, I decided to go with something cheaper. ↩

-

Based on what I had handy; this could just as well have been SPDT. ↩

-

The idea was to ultimately support up to four parameters for each effect (hence the four rotary encoders along the bottom of the screen). ↩